Philosophical Aesthetics of Graphic Design

Author: Huai-An Hsing

M.A., Institute of Philosophy of Mind and Cognition, National Yang-Ming University

I.

Functions and Aesthetic Appreciation

The purpose of graphic design is to convey messages successfully. 1

1

What is worth noting is that journalism also centers around the conveyance of messages. While closely related to graphic design, it differs in fundamental ways. Journalism involves not only the act of conveying messages but also the provision of supporting evidence behind them. In contrast, the practice of graphic design facilitates the conveyance of messages but is not itself the act of messaging. At its core, graphic design aims to ensure that audiences successfully receive specific messages through the use of various visual elements and forms.

As we know, no message will be received unless the viewer is willing to engage with it. This is why appearance often takes priority when evaluating graphic design. Aesthetic appreciation generates pleasure, and pleasure undoubtedly provides the motivation for behavior.

2

2

Refer to Gorodeisky (2019) for a theory that explains the non-contingent relationship between aesthetics and pleasure, grounded in the premise that experiencing pleasure while appreciating an object with aesthetic value is inherently worthwhile. It is important to highlight that the experience of pleasure serves as a critical source of motivation for action, with our persistent desire to browse images containing sexual content providing a striking example. However, we often avoid directly addressing this phenomenon—perhaps due to its potentially embarrassing implications—that much of our engagement in aesthetic activities stems from the pursuit of this pleasurable rush.

Nonetheless, it is worth noting that the motivational force of pleasure is not absolute. Pleasure as a motivator can be overridden by competing motives or beliefs. For instance, when faced with more pressing responsibilities, activities such as watching movies or reading novels are often postponed in favor of more urgent tasks. For further discussion on how pleasure functions as a source of motivation, see Aydede and Fulkerson (2018).

Graphic design captures attention through its aesthetic form, using visual pleasure as its allure. To understand how graphic design operates and entices viewers, we must begin with its aesthetics.

Nonetheless, it is worth noting that the motivational force of pleasure is not absolute. Pleasure as a motivator can be overridden by competing motives or beliefs. For instance, when faced with more pressing responsibilities, activities such as watching movies or reading novels are often postponed in favor of more urgent tasks. For further discussion on how pleasure functions as a source of motivation, see Aydede and Fulkerson (2018).

However, viewing graphic design purely through an aesthetic lens unfortunately conflicts with its foundational essence as a form of design. 3

3

This concern likely arises in part from categorizing graphic design within the realm of design and drawing a distinction between design and art: art is intuitively associated with aesthetics, while design is centered on functionality. Additionally, there may be a perception that aesthetic appreciation is unrelated to functionality. Since graphic design falls under the domain of design, focusing on its aesthetics might appear to disregard its functional aspects.

At the heart of design lies the need for functionality and the ideology of pragmatism, where beauty is often sacrificed in favor of practicality.

4

4

The pragmatism referenced here is not the pragmatism strictly defined by John Dewey, William James, or other philosophical traditions. What I aim to highlight is a popular ideology that influences everyday behaviors and decisions, leading people to prioritize practicality—specifically, whether something is useful or can address issues related to production and marketing—when evaluating matters. While this ideology is loosely connected to philosophical pragmatism, to my understanding, the latter does not necessarily endorse or align with the former.

For example, if a poster fails to clearly convey key information about a movie or exhibition, its visual appeal alone cannot qualify it as good design.

This brings us to the relationship of mutual antagonism between the intuitive sense of beauty and functionality. Throughout the history of philosophy, we find that conceptual antagonisms often serve as the adhesive points of an idea. By disentangling these conflicts, we can better clarify the positions of various perspectives. Using graphic design as the anchor point for analysis, I aim to focus on the “lesion” in visual culture—namely, the tension between anti-functional aesthetics and pragmatism that suppresses beauty. These two “kitsch” tendencies obscure our vision, making it harder to imagine improved approaches to seeing. 5

5

At this point, I would like to use the concept of kitsch to highlight an uncritical acceptance of popular culture or values widely embraced by the public. This includes both extremes of aesthetic belief: one that pursues “pure beauty” detached from practical or everyday purposes, and the other, which prioritizes utility above all else, dismissing beauty as nonessential and undeserving of resources. Both represent forms of aesthetic kitsch.

To my understanding, the essence of kitsch lies in the effortlessness of the behaviors stemming from these ideas. They readily provide positive rewards and satisfy desires, making them easy to adopt. However, this ease often leads to a neglect of the deeper issues inherent in these perspectives.

To my understanding, the essence of kitsch lies in the effortlessness of the behaviors stemming from these ideas. They readily provide positive rewards and satisfy desires, making them easy to adopt. However, this ease often leads to a neglect of the deeper issues inherent in these perspectives.

In the domain of analytic aesthetics, Glenn Parsons and Allen Carlson have already proposed the theory of functional beauty, which attempts to establish a connection between aesthetics and functionality. 6

6

Parsons and Carlson (2008).

This theory will serve as the foundation for the following analysis. By using it to clarify the principles and objectives of various analytical steps, while identifying potential challenges, we can refine our discourse on graphic design. Ultimately, this approach will allow us to uncover an ideal framework for examining the underlying issues hidden within the conceptual operations of graphic design.

1.

The Functional Beauty Theory

In their book Functional Beauty, Parsons and Carlson provide a detailed historical context for the way functionality has been sidelined in Western philosophical aesthetics. They critique the aesthetic tradition’s exclusive focus on art as the central object of aesthetic value. From the late 18th century—when Immanuel Kant introduced the concept of adherent beauty, treating the fulfillment of purpose as an external constraint rather than the source of aesthetic judgment 7

7

In simpler terms, Kant distinguished between two types of beauty: free beauty and adherent beauty. Free beauty does not depend on our understanding of the object’s concept—it is appreciated without preconceived notions. In contrast, adherent beauty relates to how well the object aligns with our understanding of its concept. For example, Kant considered humans, horses, and architectural structures like churches and arsenals as examples of adherent beauty.

Understanding the concept of adherent beauty is complex and remains a topic of debate in Kantian studies. For further discussion, refer to Guyer (1999).

—to the mid-20th century, when the concept of disinterestedness was embraced by aesthetic attitude theorists

8

Understanding the concept of adherent beauty is complex and remains a topic of debate in Kantian studies. For further discussion, refer to Guyer (1999).

8

Roughly speaking, the theory of aesthetic attitude posits that the essence of aesthetic experience does not lie in any inherent quality of the experience itself, but rather in the psychological attitude we adopt toward the object we are appreciating. For a detailed discussion of this theory and its interpretation of the concept of disinterestedness, refer to Stolnitz (1978).

In early philosophical aesthetics, disinterestedness was primarily understood as an appreciation of art that is unaffected by potential personal benefits the object might bring. However, proponents of the aesthetic attitude theory advocate for a broader interpretation, suggesting that disinterestedness involves approaching the aesthetic object without any predetermined purpose. This perspective reinforces the idea that the aesthetic attitude focuses solely on the aesthetic object itself. For further exploration of the term “disinterestedness” and its translation, see Chung-Ming Hsieh (1991).

—and the rise of modern art perspectives that positioned fine arts as autonomous and independent practices

9

In early philosophical aesthetics, disinterestedness was primarily understood as an appreciation of art that is unaffected by potential personal benefits the object might bring. However, proponents of the aesthetic attitude theory advocate for a broader interpretation, suggesting that disinterestedness involves approaching the aesthetic object without any predetermined purpose. This perspective reinforces the idea that the aesthetic attitude focuses solely on the aesthetic object itself. For further exploration of the term “disinterestedness” and its translation, see Chung-Ming Hsieh (1991).

9

Regarding how we can understand the concept of fine arts or high art, one can refer to this article by Szu-Yen Lin.

—functionality gradually found itself pushed to the margins of aesthetic theory.

Because this aesthetic tradition excluded functional objects like design, it failed to provide a comprehensive explanation for the aesthetics of art, nature, and everyday objects. In response, Parsons and Carlson sought to bring function back to the center of aesthetic theory. They proposed the concept of functional beauty, which holds that our aesthetic experience of an object arises from understanding how its form realizes its function. This concept can be summarized as follows:

Functional Beauty: If an object gives people the impression that its form effectively realizes a specific function, it is deemed beautiful.

Here, “form” refers to the compositional elements of an object and their interrelationships. In graphic design, these forms include the relationships between text, illustrations, layouts, and layers.

From the perspective of functional beauty, the aesthetic appeal of a thriller poster—such as Saul Bass’s design for The Shining—arises from the interplay of its formal elements. The bright red background, the unsettling squirming typography of “SHiNiNG” in mixed capitals and lowercase, and the eerie, blurry face emerging from “THE” combine to create a thrilling visual experience. 10

10

Moreover, the information, such as the director and the actors, is positioned at the bottom of the poster against a high-tone, low-chroma background. This placement separates it from the previously mentioned picture block, effectively enhancing clarity and ensuring the relevant details about the movie are clearly conveyed.

This sense of beauty is inherently tied to function. If the same design were associated with a cozy family comedy, it would appear jarring and inappropriate, detracting from its aesthetic appeal.

11

11

Parsons and Carlson offer another example to illustrate how functions influence the aesthetics of pictorial arts: if we interpret a Cubist painting, which originally evokes a sense of calm, as a representational painting from the Renaissance period, its aesthetic qualities might instead be perceived as disordered and chaotic.

The core of functional beauty theory lies in understanding how the functional category of an object influences our aesthetic appreciation. This categorization depends on the object’s proper function—that is, a function inherent to the object rather than one arbitrarily imposed. 12

12

If someone were to roll up this poster and use it to hit another person in a fit of rage, it would incidentally acquire the function of hitting people. However, when evaluating the functional beauty of an object, we focus solely on its proper functions—those inherent to the object’s intended purpose. Not all functions, especially accidental ones, influence our aesthetic experience.

For instance, a thriller poster’s proper function includes providing a thrilling visual experience.

13

13

Here, I have not provided a solid basis for this presumption. Those who argue that aesthetic experience does not encompass emotional reactions may challenge this presumption to support the claim that the sense of beauty provided by the poster leads to the thrilling experience rather than being derived from it. While I will not take a definitive stance on whether aesthetic experience includes emotional reactions, it would be an overreach to deny that the proper functions of a thriller movie poster include providing a thrilling experience. Rejecting this would risk discarding a crucial aspect of its intended purpose.

Following this line of thought, we must first determine the proper functions of graphic design to analyze its aesthetics. While graphic design may encompass multiple proper functions, the focus here is on how selecting a functional anchor can guide analysis. Through this framework, I aim to explore how the production and dissemination of graphic design within visual culture operate as an extensive apparatus for generating and exporting beauty, thereby shaping the development of visual aesthetics and our broader sense of beauty.

If we were to find an analogy for the interplay between graphic design and visual aesthetics, communication serves as an apt comparison. In communication, the speaker conveys a message to the listener, who gains a deeper understanding of the subject. A listener already familiar with the topic might wish to engage further, requiring the speaker to demonstrate greater expertise to sustain the conversation. Similarly, the interaction between graphic designers and their audiences involves this dynamic. Fortunately, visual communication has long been regarded as the proper function of graphic design. Expanding on this, design theorist Malcolm Barnard argues that visual communication engages with the beliefs and values of specific cultural groups through formal elements such as shapes, colors, lines, text, pictures, and layouts. 14

14

Refer to Barnard (2013), Chapter 9. Some have argued that visual communication encompasses multiple dimensions. Richard Hollis, for example, proposed three levels of discussion: identification, information provision and instruction, and presentation and promotion. For instance, a trademark enables us to identify the company to which a product belongs; a map provides topographical information about our location, while a road sign indicates directions to a specific destination. Meanwhile, brochures and posters present the theme and style of events or movies, aiming to capture attention and attract greater participation and consumption. See Hollis (2002), pages 9–10.

In reality, visual communication is a broad and somewhat vague concept that encompasses a wide range of practices, some of which may not relate to aesthetics. However, for the purposes of this article, I will presume that visual communication is the proper function of graphic design.

In reality, visual communication is a broad and somewhat vague concept that encompasses a wide range of practices, some of which may not relate to aesthetics. However, for the purposes of this article, I will presume that visual communication is the proper function of graphic design.

Considering an object as graphic design—where its proper function is visual communication—naturally influences our aesthetic appreciation. Before delving further into graphic design, we must first examine the details of functional beauty theory. Building on Kendall Walton’s influential article Categories of Art, Parsons and Carlson argue that the functional category of an object determines how we categorize its formal properties. 15

15

Walton (1970).

These properties are divided into three types: Standard, Variable, and Contra-Standard. Each category influences our experience of functional beauty differently.

• Standard Properties: These attributes establish the functional category of an object. For example, in graphic design, legibility is a standard property because it enables information conveyance.

• Contra-Standard Properties: These characteristics prevent an object from being attributed to a specific category. For instance, three-dimensionality is contra-standard in graphic design; an object with this property would not typically be considered graphic design, even if it conveys information. 16

16

In addition to three-dimensionality, motion is another contra-standard characteristic of graphic design in the traditional, narrow sense. However, in recent years, these two characteristics have gradually become part of graphic design practices through advancements in 3D drawing and molding software. They now serve as elements for creating experimental and dynamic tension. A notable example is the main visual poster for the 2021 Golden Horse Awards, where the additional dynamic image designed by the Bito team showcases the interaction between static graphics and motion-based media.

What is worth noting is that if more posters in the future incorporate dynamic images as a core feature, and these dynamic images even become the primary medium for realizing promotional functions, several critical questions will emerge. These include how we evaluate the original poster, whether such dynamic images can be considered graphic design, and how they connect to the aesthetic value of the original poster. These evolving practices present significant challenges for the theoretical framework of graphic design evaluation.

What is worth noting is that if more posters in the future incorporate dynamic images as a core feature, and these dynamic images even become the primary medium for realizing promotional functions, several critical questions will emerge. These include how we evaluate the original poster, whether such dynamic images can be considered graphic design, and how they connect to the aesthetic value of the original poster. These evolving practices present significant challenges for the theoretical framework of graphic design evaluation.

• Variable Properties: These attributes differentiate objects within the same functional category. For instance, color is a variable property in graphic design. Saul Bass’s The Shining poster exists in both red and yellow versions, each eliciting distinct responses based on the background color.

Understanding how an object realizes its function through form is critical for categorizing these properties. For example, without knowledge of the impact grids have on graphic design, it would be challenging to classify grids as standard, variable, or contra-standard in postmodern design. Thus, the categorization of formal properties depends on an understanding of how these elements fulfill an object’s function. Parsons and Carlson emphasize that this functional understanding profoundly shapes our aesthetic experience and identify three types of functional beauty experiences based on this framework. 17

17

What is worth noting is that the content of an aesthetic experience does not necessarily require such understanding. We do not need to consciously think about these matters in the moment of aesthetic appreciation to experience aesthetics. However, I want to emphasize that these understandings undeniably form the foundation or background for aesthetic experience. Without this prior knowledge, it becomes challenging to fully appreciate the beauty of a work. I believe this is a key reason why some experimental works often appear confusing to the general public.

1.1 Simplicity

First, when most of the formal properties of an object are standard and there is minimal variation in the variable properties, it evokes feelings of “Simplicity” and “Elegance.” Plain-colored objects typically convey simplicity because they lack complex changes in multi-colored combinations. In graphic design, plain colors limit the degree of variation in color properties, thereby creating a sense of simplicity. For example, the poster designed by Alfred Hablützel for Teo Jakob’s furniture store in Geneva in 1959 is an excellent illustration. 18

18

The title text at the top of the poster reads: “Les meubles modernes au nouveau magasin de Teo Jakob à Genève.”

The background consists of yellow and white vertical rectangular color blocks, which accentuate the table and chair composed of long black frame strips, along with text neatly organized within the central yellow block. Furthermore, the stacking of the table and chair eliminates linear perspective, emphasizing the graphic characteristics of the poster. The variable properties of this work, including color and layout, exhibit only slight variations, offering a classic sense of simplicity.

1.2 Looking Fit

An aesthetic experience of “looking fit” arises when an object displays minimal contra-standard properties and a high degree of functional variable properties. 19

19

In a previous article, I translated this concept in a way I deemed suitable at the time. However, upon reflection, I believe “looking fit” is a more accurate translation.

This concept is exemplified by the International Typographic Style, which fully embodies these characteristics. Emerging in the 1920s and 1930s, the Neue Sachlichkeit movement—reacting to expressionism—popularized the pursuit of sachlich, meaning approaching the object itself or striving for objectivity close to truth. This ideological trend influenced many graphic designers, who emphasized straightforward and clear communication with practicality as their primary goal. As a result, they opted for formal elements such as grids, photography, serif-free text, and geometric shapes.

20

20

Refer to Hollis (2006) for a detailed discussion of International Typography, also commonly referred to as the history of Swiss-style design. See pages 29–35 for insights into the correlation between the International Typographic Style and Neue Sachlichkeit.

The poster Der Massanzug kleidet noch immer am besten by Walter Käch in 1928 is a classic example of the International Typographic Style. The poster directly communicates its message—“Der Massanzug kleidet noch immer am besten”—using a rectangular block to frame a photo of hands sewing, while the remaining background space features an image resembling blue textile. The poster’s text, presented in consistent, sans-serif capital letters, ensures clarity and direct communication of the message. Additionally, the use of photography reflects the context of the time, where objectivity was increasingly valued, as photography provided a more transparent representation of objects compared to the traditional painting mediums used in earlier graphic design. This poster’s variable properties, including layout, text, and graphic material, effectively enhance the function of conveying information clearly, providing a strong aesthetic experience of looking fit. 21

21

It is worth noting that the connection between variable properties and specific functions often stems from our expectation that these properties will fulfill the intended function based on our prior knowledge. However, there is always the possibility that our understanding is flawed, or that the properties, while appearing capable, may ultimately fail to perform the function.

1.3 Tension

Perceptive tension arises when an object belongs to a specific functional category but exhibits some contra-standard characteristics or lacks certain standard characteristics. For instance, post-modern graphic design frequently abandons the grid system, employing slanted lines or curved text layouts to create an imbalanced, dynamic visual tension. This approach transforms reading into an interactive process of searching and exploration. 22

22

Graphic design directly influences reading activities, intertwining pictures and text. Despite this connection, discussions of these two media have traditionally been separate. In the latter half of the 20th century, post-modern graphic design began experimenting with merging the two. Warren Lehrer’s “Versations” (1980) brilliantly illustrates how graphic design can transform pictures into carriers of textual features and rhythmic speech, creating a playful, game-like reading experience. For further exploration of such exceptional post-modern graphic design practices, refer to Poynor (2003), particularly Chapters II and V.

The Strange Vicissitudes poster designed by Willi Kunz in 1978 exemplifies this. The design incorporates elements of the grid system from the International Typographic Style while simultaneously using slanted layouts and alternating upper- and lowercase letters in “strange VICISSIUDES,” resulting in a visually striking and tension-filled composition.

Parsons and Carlson bridge functional categories and aesthetic experiences through their proposal of three types of functional beauty experiences. This framework significantly advances the aesthetic analysis of design by emphasizing the role of function in shaping beauty. Moreover, their work highlights the philosophical implications of functional beauty: the dialectical relationship between function and aesthetics merges the values of pragmatism and beauty. This synthesis underscores that favoring one value over the other leads to misunderstandings. Overemphasizing practicality at the expense of beauty, or prioritizing aesthetics while rejecting pragmatism, hinders a comprehensive understanding of value and risks fostering a new form of fetishism.

2.

Beyond Function

A theory holds value because it provides meaning and direction for practice. The establishment of the theory of functional beauty has shifted function back to the center of aesthetics, offering an opportunity to move beyond the aesthetic tradition’s exclusive focus on art. However, in crafting the concept of functional beauty, the additional emphasis on function led Parsons and Carlson to focus primarily on aligning “beauty” with the practical aspects of design. This, in turn, overlooked design’s potential to create beauty beyond mere practicality.

A closer examination of the theory of functional beauty reveals that the examples Parsons and Carlson offer predominantly involve forms whose functions are unrelated to aesthetics, such as vehicle tires, engines, spoilers, glass doors, and furnace heads. These are elements we intuitively associate with design in practical contexts. This approach results in a framework that views design primarily through the lens of functionality-oriented objects. However, if our interest lies in design’s pursuit of beauty and its cultural significance, the analysis cannot stop here.

When considering works like the poster for The Shining or Barbara Kruger’s Untitled (Your Body Is a Battleground), created for the 1989 protest advocating reproductive freedom in Washington, are the experiences of functional beauty alone sufficient to explain the aesthetic impact? They are not. For example, the thrilling sensation evoked by The Shining poster is central to its appreciation, yet the theory of functional beauty fails to explain the connection between this sensation and aesthetic appreciation. Similarly, the beauty of Kruger’s poster arises from the profound meaning it conveys, rooted in introspection about the oppression of women’s rights under patriarchy. Functional beauty, however, does not account for how such meaning influences aesthetic experience. 23

23

Parsons and Carlson may attempt to explain the expression of a thrilling experience or the conveyance of feminist meaning through the realization of function. However, this approach fails to address the specific nature of the aesthetic experience we undergo when perceiving or understanding these elements. They might propose additional types of functional beauty experiences to remedy this limitation, but such attempts fall short when evaluated pragmatically. For an aesthetic theory to be effective within its domain, it must guide us in achieving better aesthetic appreciation. The functional beauty theory provides a framework summarizing how works convey experience or meaning. Yet, without a deeper understanding of these experiences (e.g., the thrill) or meanings (e.g., feminism)—and the ability to analyze their nuances to comprehend their existence—the sense of beauty remains elusive. Simply having the framework is insufficient. An effective aesthetic theory must begin with the experience and meaning of the work, then organize its common abstract structure to help us discern the key components of a work and why they elicit aesthetic responses. In simpler terms, understanding the concept alone does not necessarily teach us how to apply it in practice. A strong theory should enable individuals to derive conceptual understanding through engagement with practice.

Every problematic claim originates from the assumptions of its theoretical foundation. The flaws in the theory of functional beauty stem from its reliance on functionalism to explain phenomenology. Viewing function as a “black box” means we can describe inputs and outputs but lack insight into the transformative processes occurring in between. Functional beauty offers the “skeleton” of design practice—how materials (graphics, text, etc.) are assembled via forms like layers and relationships to achieve a specific function, such as conveying a message. However, it neglects the “tissue” that fills this skeleton: the beauty or meaning imbued by the materials themselves, which undeniably influences aesthetic appreciation. 24

24

The works discussed in this article exemplify cases where the aesthetics of photographic materials significantly influence our appreciation of the works. This influence is undeniable. However, whether the beauty of these materials can be considered an intrinsic part of the practice of graphic design may invite further debate. This question forms the central focus of the next section.

Graphic design transforms these elements into cohesive experiences, but without analyzing the input materials, we cannot understand the transformations that occur, leaving aesthetic explanations hollow.

Parsons might counter this criticism by arguing that the theory’s limitations are not its fault, as the experiences provided by materials are unrelated to the aesthetic appreciation of graphic design itself. This argument is rooted in the presumption that the object and practice of graphic design are separate. When treating graphic design as an object, we may appreciate the visual experiences it offers, but the practice of graphic design is not about creating those experiences. This ontological stance is elaborated in Parsons’ The Philosophy of Design, where he posits that design practice creates not the object itself but the plan for its creation. Similar to an architect who designs a building but does not construct it, the graphic designer’s role is primarily conceptual. 25

25

Parsons (2015), Chapter I.

Understanding graphic design as planning reframes it as a practice of utilizing materials rather than creating them. 26

26

As stated in The Elements of Graphic Design by Alex White, graphic design (and other forms of design) involves assembling unrelated parts into an organized whole. Refer to White’s Foreword (2011). Notably, when graphic designers integrate materials to create a complete visual composition, this composition may, in turn, serve as a material for other creators. However, graphic design itself does not aim to produce materials but rather to organize them into meaningful forms.

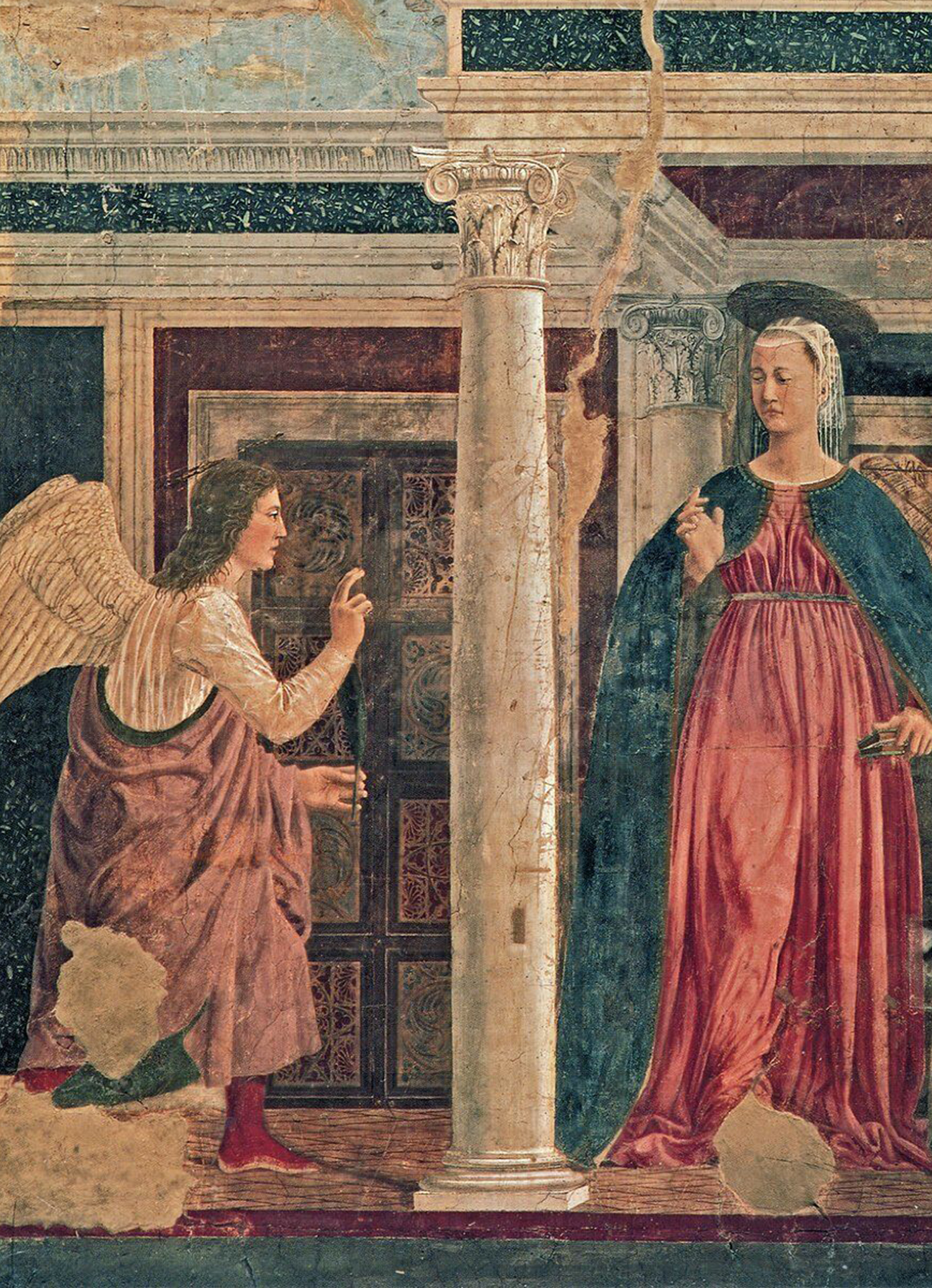

This perspective helps distinguish graphic design from visual art. While some visual arts also serve the function of visual communication—such as Western religious paintings that convey the Vatican’s beliefs through color and line—they are not categorized as graphic design. Painting on canvas or modeling objects using software may fulfill communicative functions but remain distinct from graphic design, which focuses on how these creations are used as part of a plan.

27

27

Viewed from this perspective, even the artists of religious paintings engaged in a practice akin to graphic design. For example, they selected paints, much as graphic designers choose colors and textures for specific elements. Similarly, they conceptualized religious narratives, akin to how graphic designers synthesize materials into cohesive visuals based on client requirements.

This planning perspective also illuminates the historical evolution of graphic design. For instance, Dada’s photomontage and modern collage art—often cited as precursors to contemporary graphic design—emphasize the assembly of found objects rather than their inherent beauty. However, this does not imply that aesthetic experiences derived from materials should be dismissed when analyzing graphic design. While the creation of materials falls outside the scope of graphic design, the designer’s selection and use of materials directly contribute to the aesthetic experience. 28

28

Parsons introduces another layer of presumption regarding the connection between the aesthetic experience of materials and the evaluation of graphic design. He argues that the concept of design involves a rational relationship between the end product and the design process. Specifically, the intended purpose of the final product informs and guides the entire design process. Parsons explains this through the concept of “problem and solution,” aligning with the common understanding of design as a means of solving problems. Under this framework, the evaluation of graphic design appears focused solely on whether it effectively resolves the problem of visual communication. While graphic designers can address this problem through the aesthetic experience offered by materials, the emphasis in such cases shifts to whether the aesthetic experience effectively solves the communication problem, rather than the intrinsic aesthetic value of the materials themselves.

Selecting appropriate materials is a critical aspect of graphic design practice. If the designer’s goal is to create an aesthetic experience, the beauty of the materials becomes essential. Even seemingly mediocre materials can be elevated under the designer’s aesthetic vision, becoming integral to the overall plan. While graphic design does not always involve creating materials, it invariably involves selecting and incorporating them. Neglecting the aesthetic experience of the materials themselves means failing to fully appreciate how the design fulfills its function of providing an aesthetic experience. Without this understanding, we cannot comprehend how the designer achieves the intended outcome.

3.

Open the Black Box

The core problem with the functional beauty theory lies in its understanding of design as a type of plan, distinct from the act of creating materials. Parsons and Carlson, when filling in the content of this plan with practicality-based examples, focus on designs whose main objective is not the pursuit of beauty. As a result, the sense of beauty is not prioritized in the selection of materials. Consequently, the functional beauty framework sacrifices the sensory experiences and meanings that design can offer. 29

29

Broadly speaking, the concept of craft can be used to describe actions that endow concrete entities with functional properties, allowing us to intuitively understand art as a specialized form of craft. The distinction between art and other crafts lies in their objectives: art creates objects with aesthetic functions, whereas other crafts introduce functions unrelated to aesthetic appreciation. The actions performed under plans created by designers typically fall under craft practices that do not inherently provide an aesthetic experience. This distinction explains why functional beauty theory adequately addresses such examples. When appreciating these designs, we might experience the results of craft practices, but these experiences remain outside the realm of aesthetics. Consequently, the sense of beauty they offer is limited to the experience of functional beauty. For a detailed discussion on the relationship between craft and art and the connection between aesthetic experience and the function of art, refer to Zangwill (2007), pp. 160–166.

If a designer creates with beauty as a goal—where the functions of the design include providing an aesthetic experience—then the beauty of the materials becomes a critical consideration. Their aesthetic value inevitably influences how we evaluate the work. While it is unreasonable to criticize a designer for not creating materials from scratch, the use of subpar materials undeniably poses an issue for the design.

30

30

It is important to note that the aesthetics of material usage differs from the aesthetics of material creation. The latter pertains to visual art, while the former is associated with graphic design. When we appreciate a work as visual art, we are evaluating the beauty it conveys based on fundamental knowledge of how and why its materials were created. In contrast, when we appreciate a work as graphic design, our focus shifts to understanding how and why the materials were employed in a particular way.

I aim to highlight the potential of this practice and propose a theoretical framework to better understand its aesthetics. Some might argue that if the beauty of materials contributes to the aesthetic experience of graphic design, then how does this differ from the aesthetics of visual art? The distinction, I believe, lies in the focus of appreciation. In visual art, such as paintings, the aesthetic qualities of the picture itself command our primary attention. By contrast, when a poster incorporates a painting, we do not focus on how the form of the painting fulfills its function in isolation.

Instead, the aesthetic experience of such a picture functions as a background element, integrated with other materials. Our attention shifts toward understanding how these visual elements combine into a cohesive form, producing an overall aesthetic experience. When appreciating a work as graphic design, the resulting aesthetic experience emerges from the interplay between the background (the picture) and the foreground (other elements). 31

31

For a theoretical foundation on the distinction between foreground and background in the experience of attentional operation, refer to Watzl (2017).

The materials used in graphic design often derive from the broader pictorial arts tradition, including paintings, photography, and other forms of visual art. Since the aesthetic experiences provided by these materials form the foundation for graphic design, an appreciation for beauty within pictorial arts becomes a key professional competency for graphic designers. In this sense, a professional graphic designer can be regarded as an ideal embodiment of the aesthetic subject.

32

32

Critics may argue that designers are predominantly client-oriented, with only a small minority prioritizing aesthetics. While it is true that most designers primarily address client needs, the history of graphic design includes theorists who contend that designers have an obligation to enhance the general public’s aesthetic sensibilities. Although this is a bold claim, even without such an obligation, it is reasonable to regard this as a value inherent in the practice of graphic design. The concept of self-authorship, which emerged in graphic design at the end of the 20th century, further supports the idea of separating graphic design from client-driven constraints. This concept highlights the importance of independent creative practices in the education and evolution of graphic design. For further insights, see Burdick (1993) and Rock (1996).

Having established the foundational content for the aesthetic experience of graphic design, we can now consider how to evaluate its aesthetic value. In the next article, I will explore how aesthetic theory can guide the creation of a system for evaluating the aesthetics of graphic design. Given that the aesthetic appreciation of materials shapes how we evaluate graphic design in terms of its capacity to provide an aesthetic experience, we must begin by analyzing how these materials compose the overall picture presented to us, generating a unified sense of beauty.

Merely analyzing the transformation from input to output is insufficient to comprehend the operations within the “black box” of design. These transformations are grounded in the input data, and the “black box” can only be revealed through epistemological descriptions of this data. When the input material in graphic design consists of visual art, phenomenological analysis of these materials is essential to establish the knowledge base for evaluating their aesthetic value.

To address this, I will introduce the concept of pictorial analysis as practiced by visual art historians, highlighting its two layers. The first layer pertains to the aesthetic experience of the picture itself, while the second focuses on how the picture is utilized within a broader context. I will demonstrate how the first layer can be integrated into the framework of graphic design aesthetics, addressing the omissions in functional beauty theory. Furthermore, I will argue that the second layer represents the core of aesthetic appreciation in graphic design and provides a bridge between the two layers of analysis. By examining this transition, we can develop a more comprehensive understanding of how the aesthetic value of graphic design emerges from its materials and their application.

References

Aydede, M., & Fulkerson, M. (2018). Reasons and theories of sensory affect. In Philosophy of Pain (pp. 27-59). Routledge.

Barnard, M. (2013). Graphic design as communication. Routledge.

Burdick, A. (1993). What has writing got to do with design? Eye, 3(9), 4–5.

Gorodeisky, K. (2019). The authority of pleasure. Nous, 55(1), 199–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/NOUS.12310︎︎︎

Guyer, P. (1999). Dependent Beauty Revisited: A Reply to Wicks. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 57(3), 357. https://doi.org/10.2307/432200︎︎︎

Hollis, R. (2002). Graphic design : a concise history. Thames & Hudson.

Hollis, R. (2006). Swiss graphic design: the origins and growth of an international style, 1920-1965. Laurence King Publishing.

Parsons, G. (2015). The philosophy of design. John Wiley & Sons.

Parsons, G., & Carlson, A. (2008). Functional beauty. Oxford University Press.

Poynor, R. (2003). No more rules: graphic design and postmodernism. Laurence King Publishing.

Rock, M. (1996). The designer as author. Eye, 20(5).

Stolnitz, J. (1978). “The Aesthetic Attitude” in the Rise of Modern Aesthetics. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 36(4), 409. https://doi.org/10.2307/430481︎︎︎

Walton, K. L. (1970). Categories of Art. The Philosophical Review, 79(3), 334. https://doi.org/10.2307/2183933︎︎︎

Watzl, S. (2017). Structuring mind: The nature of attention and how it shapes consciousness. Oxford University Press.

White, A. W. (2011). The elements of graphic design: space, unity, page architecture, and type. Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.

Zangwill, N. (2007). Aesthetic creation. Oxford University Press.

Chung-Ming Hsieh (1991), The aesthetic status of disinterestedness – 165-176, Scroll 1 of Tunghai Journal of Philosophy.

Aydede, M., & Fulkerson, M. (2018). Reasons and theories of sensory affect. In Philosophy of Pain (pp. 27-59). Routledge.

Barnard, M. (2013). Graphic design as communication. Routledge.

Burdick, A. (1993). What has writing got to do with design? Eye, 3(9), 4–5.

Gorodeisky, K. (2019). The authority of pleasure. Nous, 55(1), 199–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/NOUS.12310︎︎︎

Guyer, P. (1999). Dependent Beauty Revisited: A Reply to Wicks. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 57(3), 357. https://doi.org/10.2307/432200︎︎︎

Hollis, R. (2002). Graphic design : a concise history. Thames & Hudson.

Hollis, R. (2006). Swiss graphic design: the origins and growth of an international style, 1920-1965. Laurence King Publishing.

Parsons, G. (2015). The philosophy of design. John Wiley & Sons.

Parsons, G., & Carlson, A. (2008). Functional beauty. Oxford University Press.

Poynor, R. (2003). No more rules: graphic design and postmodernism. Laurence King Publishing.

Rock, M. (1996). The designer as author. Eye, 20(5).

Stolnitz, J. (1978). “The Aesthetic Attitude” in the Rise of Modern Aesthetics. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 36(4), 409. https://doi.org/10.2307/430481︎︎︎

Walton, K. L. (1970). Categories of Art. The Philosophical Review, 79(3), 334. https://doi.org/10.2307/2183933︎︎︎

Watzl, S. (2017). Structuring mind: The nature of attention and how it shapes consciousness. Oxford University Press.

White, A. W. (2011). The elements of graphic design: space, unity, page architecture, and type. Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.

Zangwill, N. (2007). Aesthetic creation. Oxford University Press.

Chung-Ming Hsieh (1991), The aesthetic status of disinterestedness – 165-176, Scroll 1 of Tunghai Journal of Philosophy.

Copyright © 2019–2024 Taipei Art Direction & Design Assoc. All rights reserved.

Website designed and developed by Yaode JN︎︎︎. Running on Cargo︎︎︎.

Website designed and developed by Yaode JN︎︎︎. Running on Cargo︎︎︎.

Copyright © 2022 Taipei Art Direction & Design Assoc. All rights reserved.

Website designed and developed by Yaode JN︎︎︎. Running on Cargo︎︎︎

Website designed and developed by Yaode JN︎︎︎. Running on Cargo︎︎︎