Philosophical Aesthetics of Graphic Design

Author: Huai-An Hsing

M.A., Institute of Philosophy of Mind and Cognition, National Yang-Ming University

II.

Styles and Genres

In the previous article, I explained the functions of graphic design through the lens of visual communication. I then reviewed the theory of Functional Beauty by Glenn Parsons and Allen Carlson to establish a connection between functionality and aesthetic experience, using the relationship between visual communication and aesthetic appreciation as a starting point for analyzing the aesthetics of graphic design.

The functional beauty theory contributes significantly by showing how understanding the functional category of a work enables us to categorize its formal elements based on their relevance to fulfilling the intended function. This categorization helps explain the aesthetic experience through the influences these formal elements exert. Thus, when appreciating a graphic design, we must first understand how the work achieves its visual communication objectives to make a well-informed aesthetic evaluation.

However, the functional beauty theory has its limitations. It explains the aesthetic experience of design solely by assessing whether the form aids in realizing the function, neglecting designs where aesthetic appreciation stems from the experiences provided by the materials themselves. Consequently, the theory excludes the aesthetic experience of the material from its framework, failing to fully account for the sensory experiences and meanings introduced by graphic design.

Certainly, what we care about is not the isolated aesthetic experience of individual materials. For instance, if a poster incorporates a photograph, our concern is not the photograph’s aesthetic experience per se—that is a matter for the aesthetics of visual art. Instead, the aesthetics of graphic design must address how the aesthetic experience of the photograph integrates with experiences from other materials to form a cohesive whole that warrants aesthetic appreciation.

To achieve this, we need to establish a foundational knowledge base. This involves understanding the materials graphic designers select for different visual communication objectives and analyzing the patterns used to assemble these materials into a unified picture that conveys an aesthetic experience. This necessitates an analysis of patterns in images to clarify their evolution and derive systematic insights from past graphic design works. In other words, we must undertake a historical analysis of these image-making practices to uncover how they create beauty. This requires a methodology rooted in the history of graphic design. 1

1

The emergence of modern graphic design is a relatively recent historical development, making the field of graphic design history both nascent and still evolving. As a result, the study of graphic design history remains a developing discipline, and debates about how to approach and understand it are ongoing. The development of methodologies for this field is similarly in its early stages. For further discussion on these issues, refer to Triggs (2009, 2011).

1.

Iconography and Iconology

Our objective is to reintegrate the sense of beauty derived from materials into the aesthetic experience of graphic design. The foundational step in building the required history of graphic design involves conducting phenomenological descriptions of images composed using these materials and documenting how their patterns have evolved over time. This historical inquiry is essential, as philosophical analysis does not emerge solely from abstract concepts but from extracting raw material from practice and abstracting it into knowledge. By tracing the historical practices, we uncover the foundations of philosophy, which are shaped by the historical context in which they arise.

What is needed is a historical methodology capable of documenting and analyzing the aesthetic experiences provided by these images, while also explaining why they appear in specific historical contexts and what meanings they hold. This is the task already being undertaken by the history of visual arts. The overlap is unsurprising since the aesthetic experiences omitted by functional beauty theory are often treated as the domain of art. By integrating art historical methods into the aesthetic analysis of design, we can construct the contextual foundation for aesthetic vision through the aesthetic experiences of the materials. 2

2

I believe that this approach is not limited to graphic design. It can be extended to other design fields by substituting visual art history with the corresponding art history for the specific design domain.

Visual art history has a long-standing tradition of describing and interpreting the experiences and patterns of images—a practice known as iconography. Erwin Panofsky significantly contributed to this field by distinguishing between iconography and iconology. The difference can be likened to the distinction between ethnography and ethnology: ethnography focuses on documenting and organizing the details of an ethnic group’s life, while ethnology compares this culture to those of other groups. Similarly, iconography describes the aesthetic experiences elicited by images, whereas iconology delves into the social and cultural meanings behind those images. 3

3

According to Panofsky, iconography is fundamentally descriptive, focusing on documenting what is observed, whereas iconology is interpretive, analyzing deeper meanings and contexts. For further details, see Panofsky (1983), pp. 26–54.

Panofsky further divided the practices of art history into three levels:

1. Pre-iconography: Focuses on identifying objects or events represented by artists through specific formal elements.

2. Iconography: Explains the narratives, motifs, or themes arising from the combination of these objects or events.

3. Iconology: Analyzes the symbolic meanings and cultural contexts embedded in the images.

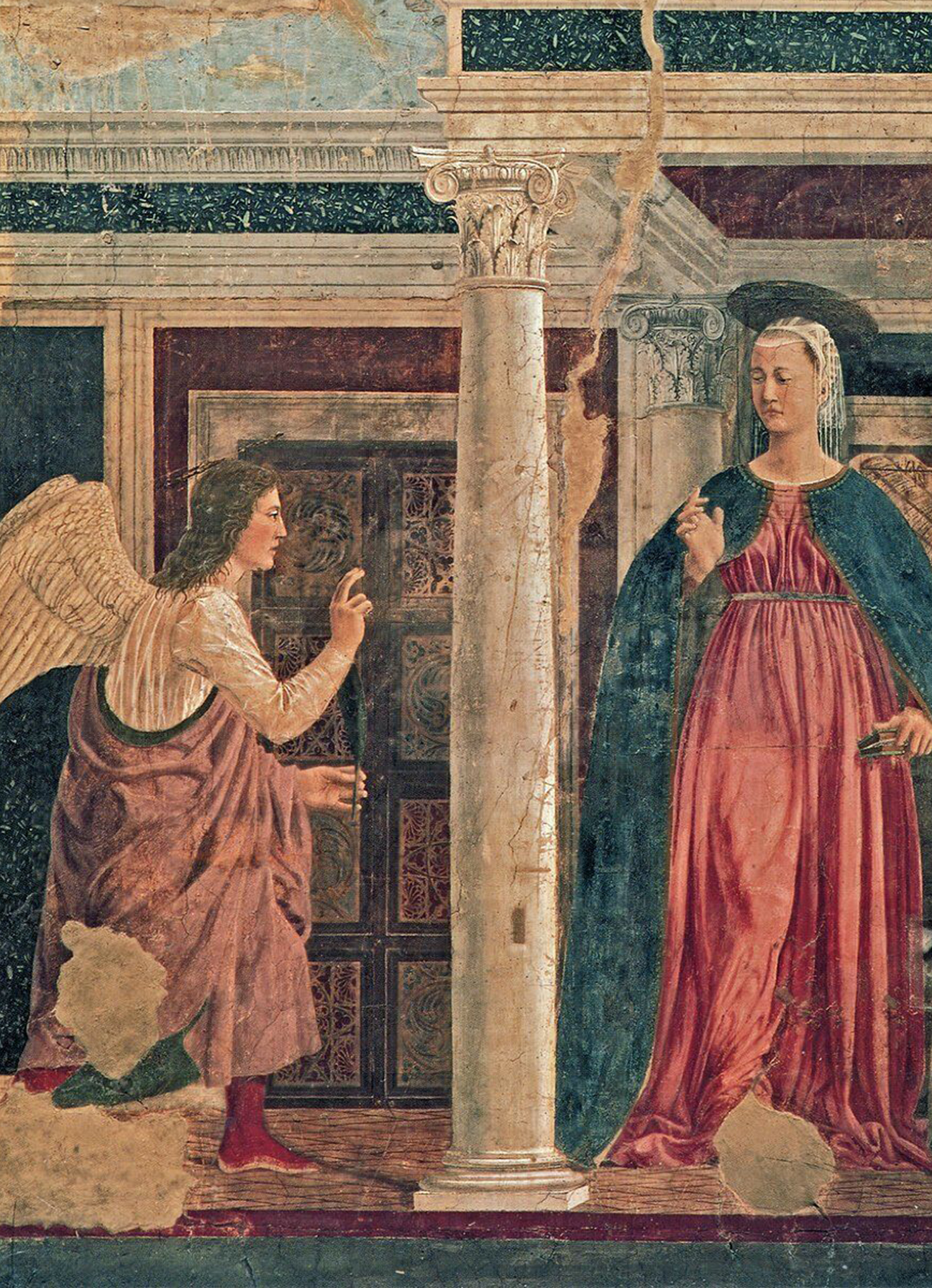

For example, at the iconographic level, in Sandro Botticelli’s Cestello Annunciation (c. 1489), we can identify the figure on the left as the angel Gabriel, distinguished by his wings, and the figure on the right as the Virgin Mary, identified by her halo, blue robe, and red lining. The angel holds lilies and leans toward Mary, seemingly delivering a message.

Through iconography, art historians interpret these elements as depicting Gabriel announcing to Mary that she will bear God’s child, with lilies symbolizing her purity. This interpretation organizes the thematic pattern: The Annunciation. At the iconological level, deeper questions emerge: What theological significance does Cestello Annunciation hold within Christianity? What meanings are conveyed by Botticelli’s depiction of Mary’s posture and expression—showing hesitation, tension, and even anxiety—elements absent in earlier works?

Panofsky’s differentiation of the three levels—pre-iconography, iconography, and iconology—is not without its limitations. It is challenging to strictly separate pre-iconography from iconography, as identifying the objects or events depicted in a picture often requires some understanding of its narrative or theme. Additionally, iconological assumptions about the symbolic meanings or cultural context of a picture can influence interpretations at the iconographic level. However, the aim here is not to delve into debates about the methodological nuances of art history. Instead, this framework serves as a prototype for outlining the practices of pictorial art history and exploring its relationship with the aesthetics of graphic design.

Through the documentation of iconography, we can trace how pictures with specific themes evolve through art history, acquiring unique forms and styles. For instance, in Renaissance Italy, The Annunciation was depicted in distinct ways by artists such as Piero della Francesca (c. 1455), Domenico Veneziano (c. 1445), Filippo Lippi (c. 1440), and Botticelli. Each version provides distinct aesthetic experiences, including balanced composition, the interplay of outdoor lighting and spatial arrangement, detailed perspective structures, and the affetti (expressive bodily dynamics) of the figures. 4

4

For a classic iconographic study of Cestello Annunciation, refer to Robb (1936).

This example demonstrates how the practice of iconography systematically documents and interprets the aesthetic experiences created by images with diverse themes and styles. For graphic design, aesthetic analysis depends on understanding how designers employ specific patterns to integrate different pictorial materials into a cohesive aesthetic whole. Consequently, the establishment of iconography forms the cornerstone of developing a robust aesthetic framework for graphic design. 5

5

It is important to note that applying iconography to graphic design involves analyzing not only the “picture” itself but also the broader context of information conveyance. As media evolves, so does the method of communication. Consequently, the history of graphic design can be roughly divided into two major periods: before and after the advent and popularization of computers. At this level, the iconography of graphic design also serves as a record of the evolution of visual media.

To apply iconography to graphic design, we must first categorize its various themes, identify works that represent these themes in graphic design history, and then conduct phenomenological descriptions of their visual compositions.

How, then, should we categorize the themes of graphic design images? The purpose of analyzing themes is to group works with similar purposes into the same category, enabling systematic comparison. Iconography facilitates the organization of designs with shared themes, allowing for an evaluative framework that can distinguish better designs from less effective ones.

By analyzing the functions of graphic designs within different themes, we can assess their aesthetic value based on the successful realization of their intended functions. Additionally, this approach helps us identify how different patterns either aid or hinder the fulfillment of these functions, ultimately contributing to a more nuanced understanding of graphic design’s aesthetic and functional interplay.

Therefore, the differentiation of themes serves to categorize pictures according to their functions. A specific function imbues a creation with meaning. By understanding the function of an object, we gain a foundational understanding of its existence. Similarly, clarifying the individual functions of a graphic naturally delineates its theme. Conversely, when analyzing the themes of graphic design images through functional analysis, our focus shifts to understanding why the designer chose a particular approach and how audiences interpret the design. This line of inquiry seeks to uncover the cultural context that inspired the creative motivation and assess the impact of the work on the history of graphic design and visual culture.

Thus, the investigation into the existence of a graphic constitutes a form of iconological practice. W.J.T. Mitchell provides a pivotal explanation of iconology, describing it as the exploration of the concept of the picture and an effort to explain what a picture is. 6

6

W.J.T. Mitchell distinguishes between the concepts of image and picture. Simply put, a picture refers to a tangible, material creation, whereas an image is the abstract entity we experience through a picture. In Mitchell’s analysis of icons, which incorporates both the meanings of image and picture, he predominantly discusses image when addressing iconology. However, for the sake of clarity and consistency, I will translate his term as iconology throughout. In this section, the term picture encompasses the meaning of image. For further details, refer to Mitchell (1987), pp. 1–6, and Mitchell (2015), Chapter II.

In essence, iconology is the study of the picture itself—a philosophical inquiry into the nature of the image. As a branch of philosophy, iconology not only examines the essence of pictures but also investigates their production processes and cultural meanings.

7

7

Mitchell’s conceptualization of iconology as a philosophy of the picture is most evident in the introduction to his groundbreaking work, Iconology. Beyond defining iconology as the theoretical study of the picture itself, he announces his intention to explain how we comprehend pictures by analyzing their use across disciplines such as literary criticism, art history, and philosophy. Although Mitchell identifies as a historian, he later references the development of a science of the picture in subsequent publications. This approach can be seen as philosophical in nature. Furthermore, Mitchell’s concept of science is not rooted in positivism but aligns more closely with the Wissenschaft tradition in German intellectual history. In my view, many contemporary philosophical practices share this purpose. Mitchell not only granted iconology a philosophical status but also connected it to totemism, fetishism, and idolatry, thereby situating it within a broader philosophical and historical context. For a detailed discussion, see Mitchell (1987).

This perspective highlights that iconological analysis is a vital method for understanding what functions a picture serves and why it serves those functions. The relationship between theme and function operates as two sides of the same coin: while a theme assigns a specific function to a picture, clarifying the function helps identify its theme. This interdependent relationship underscores the mutual importance of iconography and iconology in establishing the aesthetics of graphic design. Together, they provide a comprehensive framework for analyzing both the visual and cultural dimensions of graphic design.

2.

Categories of Graphic Design

At this point, I hope to have outlined a clear pathway for understanding the aesthetics of graphic design, rooted in the historical and philosophical practices of iconography and iconology. The aesthetics of graphic design centers on whether the overall picture, composed of visual materials with specific patterns, successfully realizes its intended function. Iconography helps us categorize graphic design works based on specific themes, while iconology enables us to clarify the functions of these works.

To develop a comprehensive aesthetic theory of graphic design, two additional steps are required:

1. Progressing from iconographical analysis to iconology—establishing the connection between a graphic’s theme and its function.

2. Evaluating whether the graphic has successfully realized its intended function after the function is clarified.

The latter will be addressed in the next article, where I will explore how the realization of functions informs the aesthetic value of graphic design. For now, we will focus on the former and continue with the current analysis.

Determining the theme of a graphic does not automatically provide insight into its context or meaning. Images sharing the same theme can convey entirely different messages depending on the creator. For example, René Magritte’s La Trahison des Images features an image of a pipe, yet its accompanying text, “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (“This is not a pipe”), subverts the expectation of literal representation. 8

8

Some might argue that in La Trahison des Images, Magritte’s statement, “This is not a pipe”, merely reflects the contradiction between the text and the image of the pipe, suggesting that the picture still represents a pipe while the text creates the illusion of negation. However, the image of the pipe itself is a crucial element provoking the audience to imagine that it is not a pipe but something else. If the object depicted in the painting did not resemble a pipe, viewers would naturally interpret the text as confirming this lack of resemblance. Yet such a scenario would strip the original painting of its rebellious tension. This example is included here to illustrate the interaction between image and meaning in a broader context.

E.H. Gombrich argued that before delving into the meaning of a picture, we should evaluate whether specific formal elements adhere to established rules for conveying the artist’s (or sponsor’s) intended message.

9

9

ombrich critically examines the aims and limitations of iconology in Chapter I, “The Aims and Limits of Iconology,” of his book Symbolic Images (1972). For further reference, see Gombrich (1972).

A picture’s meaning is not dictated by its theme alone but by our assumption about the message the artist intends to communicate through that theme. 10

10

Determining a work’s meaning and the role of the creator’s intention are central topics in the philosophy of literature, and many scholars agree that these discussions can be extended to other art forms. Although this article series does not aim to delve into the creator’s intention specifically, I recognize the potential for confusion regarding my stance and offer clarification here.

In simple terms, debates on this issue can be grouped into two camps: intentionalism and anti-intentionalism. Anti-intentionalists argue that it is unnecessary to consider the creator’s intention when interpreting a work’s meaning. Intentionalists, on the other hand, assert that the creator’s intention contributes to a work’s meaning, though they differ on how this is determined. Among intentionalists, actual intentionalists hold that the meaning of a work should correspond to the creator’s actual intentions, while others argue that creator-related factors are based on our assumptions or imagination.

While I do not adopt a stance of actual intentionalism, I do believe that art historical practices strive to reconstruct the message the creator intended to convey by examining historical data, as this affects how we interpret and evaluate a work. However, the narrative provided by art historians cannot claim to represent the creator’s actual intention unequivocally; instead, it might involve assumptions, imaginative interpretations, or other possibilities.

Although I do not oppose anti-intentionalism, I find that neither anti-intentionalism nor modest forms of actual intentionalism—where unintended elements are used to compensate for gaps in the creator’s intention—are particularly helpful in this context. My aim is for readers to grasp the general intuitions I hold about this topic, with the understanding that detailed exploration can occur in a future discussion.

Since an artist’s intention cannot be directly accessed, we must rely on historical data and identify the rules by which specific pictorial patterns convey messages. By organizing works with similar formal elements and purposes in art history, we can speculate on the functions of a given picture. These rules create a link between the artist’s intention and the formal elements of the work, allowing us to categorize historical artworks into distinct clusters. Each cluster corresponds to different functions.

11

In simple terms, debates on this issue can be grouped into two camps: intentionalism and anti-intentionalism. Anti-intentionalists argue that it is unnecessary to consider the creator’s intention when interpreting a work’s meaning. Intentionalists, on the other hand, assert that the creator’s intention contributes to a work’s meaning, though they differ on how this is determined. Among intentionalists, actual intentionalists hold that the meaning of a work should correspond to the creator’s actual intentions, while others argue that creator-related factors are based on our assumptions or imagination.

While I do not adopt a stance of actual intentionalism, I do believe that art historical practices strive to reconstruct the message the creator intended to convey by examining historical data, as this affects how we interpret and evaluate a work. However, the narrative provided by art historians cannot claim to represent the creator’s actual intention unequivocally; instead, it might involve assumptions, imaginative interpretations, or other possibilities.

Although I do not oppose anti-intentionalism, I find that neither anti-intentionalism nor modest forms of actual intentionalism—where unintended elements are used to compensate for gaps in the creator’s intention—are particularly helpful in this context. My aim is for readers to grasp the general intuitions I hold about this topic, with the understanding that detailed exploration can occur in a future discussion.

11

While we can never be entirely certain of an artist’s intention, this does not negate the importance of the creator’s intention in shaping the function of a work. To analyze the functions of a specific formal element, it is crucial to understand the creative purpose behind it. The apparent motive behind the creator’s choices influences our aesthetic experience and evaluation of the work.

To formalize this approach, the next step involves using a conceptual framework to abstract the clusters identified through these rules. In literary criticism, the concept of genre has long served this purpose. Gombrich applied the concept of genre to the study of visual art history, introducing a systematic way to connect clusters of works with their respective functions. 12

12

Same as note 7.

So, how should the genre of graphic design be distinguished? 13

13

Certainly, we might instinctively consider using various “-isms” for categorization. For instance, if we categorize La trahison des images as part of the surrealism genre, we can interpret its meaning correctly. However, if it were treated as realism, our interpretation and evaluation would be misguided. We can reference these “-isms” because they have been established over the long history of art. As long as creators continue to produce new images, we are likely to encounter works that do not fit neatly into existing “-isms.” It is also worth noting that there are far fewer “-isms” in the history of graphic design to categorize compared to painting. The concept of “-ism” is broad, and what we truly need to understand is the principles behind the categorization of “-isms” and use those principles to explore the functions of images.

One method is to group works with similar functions, analyze their forms, and identify their common elements or features, which can then be used to define the genre. Gombrich taught us that the importance of genre lies in connecting the theme of the picture with the creator’s intention. The concept of genre must be thoroughly explained to describe how it will affect our interpretation of the work. According to this perspective, when we categorize a work into a particular genre, it means that it possesses the formal elements that define that genre. Therefore, we anticipate these elements to carry specific creative intentions and propose corresponding interpretations of the work.

In the previous article, we discussed the poster designed by Saul Bass for the movie The Shining. Based on elements such as its colors, text, and composition, we would undoubtedly categorize it as a thriller movie poster. Thus, we expect this poster to evoke a sense of anticipation for the movie by providing a thrilling experience, and we interpret its formal elements as intended to provoke fear and anxiety. However, although some works belong to a specific genre, they do not necessarily feature certain formal elements that should belong to that genre.

For example, the poster for the movie Hereditary, designed by the graphic design company Gravillis Inc., features a model house with bright lights at night, where the color and brightness of the lights in all rooms appear almost constant. Some rooms defy gravity, rotating 90 or 180 degrees. The people inside are figurines, seemingly lost in their own worlds, creating an image that evokes feelings of treachery rather than fear or anxiety. Even though this work is categorized as a thriller movie poster, it does not feature the typical frightful elements. If we compare the Hereditary poster with the expectations we have for The Shining poster, we might feel that the Hereditary poster fails to do what a thriller movie poster is supposed to do, but this reaction would clearly be unreasonable. This shows that it is difficult for us to identify a set of common formal features in these posters defined as the thriller movie genre.

Certainly, we can subdivide a genre into other sub-genres. However, this will not solve the current issue. Differentiating sub-genres can allow us to better understand the creative intentions behind works in each sub-genre, but it does not help explain how the original genre affects interpretation. The reason why genre evaluation influences the interpretation of works is that when we categorize a work into a certain genre, we expect it to fulfill the functions that belong to that genre. However, different formal elements can realize the same function. Therefore, it becomes difficult for us to demarcate a set of formal elements to define a specific genre. However, everything becomes much easier if, in reverse, we determine the genre through the functions of the work, and then select the formal elements related to realizing that function. 14

14

Please refer to Abell (2015) regarding how genre affects our interpretation and evaluation of works.

3.

From Style to Genre

Works within the same genre may serve different functions, but they must share a core function to be classified under the same genre. To identify this core function, we need an anchoring point that unites similar works. If our focus is graphic design aimed at providing an aesthetic experience, the most intuitive approach is to identify the shared function among works that deliver a comparable experience. This approach aligns with practices in aesthetics and criticism: when we appreciate or critique a work, we typically compare it with other works that evoke a similar aesthetic experience.

To describe the shared aesthetic experience of a group of works, the concept of style naturally comes to mind. If we can categorize functions common to a group of works distinguished by style, these functions will offer the best definition for the genre of that group. The crucial task, then, is to establish a visible connection between a work’s style and its function. Achieving this requires analyzing how style is formed and identifying the core factor that enables a work’s function within the causal chain that shapes its style.

We attribute a work to styles such as American Art Deco or Internationalism because of certain formal features that elicit specific experiences. Some works possess these features because the designer intentionally chose to incorporate them. When appreciating such works, we not only perceive their style but often infer the motives underlying the creation of that style. Creations within the same style can have diverse objectives: some may employ certain elements to explore experimental possibilities, while others may use them to evoke nostalgia. This demonstrates that aesthetic experiences are shaped by the formal elements of a style and by the audience’s interpretation of the creator’s motives. Kendall Walton articulated this by examining the expressive qualities of works, thereby bridging philosophical aesthetics and the philosophy of art. 15

15

Refer to Walton (1987) for a detailed explanation of the concept of style and its relationship with expression.

As Walton reminds us: “… style is not expression but the means of expression.” 16

16

Same as the previous note, page 94.

A work belongs to a particular style due to its specific features, but this merely signifies its potential to express a particular aesthetic experience. The audience’s interpretation of the creator’s motives is what actualizes that expression. By understanding how an audience anticipates the creator’s intent, we can uncover how a work, through its stylistic forms, conveys its function. This reveals the connection between style and function: the perceived motive behind the creative act, which endows the work with its style, becomes the key determinant of its function.

17

17

It is important to note that the style of a work is not entirely determined by the creator’s intention. For example, if an artist aims to create an Impressionist painting but instead evokes an Expressionist aesthetic, it would be incorrect to claim that the painting has an Impressionist style. The actual function realized by a work does not always align with the function the creator intended. As Walton explains, analyzing style brings us into contact with a “superficial author”—a construct of the audience’s interpretation—that may not fully coincide with the creator’s actual intent. Nonetheless, this “superficial author” provides a framework that enables us to associate the creative process with the forms manifested in the work.

As compared to an analysis that begins with formal features, starting with an examination of the creative actions offers a distinct theoretical model. Instead of first identifying a cluster of formal features and then attempting to classify works into genres, this approach begins with the actions that produce the significant formal elements of a work. From these actions, we piece together the aesthetic experiences the work generates and align them with an abstract conception of genre.

This method does not presuppose the existence of overarching genres that must later be subdivided into sub-genres. Instead, it clarifies the purposes of specific creative actions, determines the (sub-)genre through this analysis, and then examines the activities involved in the creative process. Using this framework, genres previously identified can help uncover the functions of a work. This approach also allows us to observe whether common creative methods and techniques enable works with specific sub-genre functions to coalesce into larger genres.

To illustrate, let us analyze the poster designed by Armin Hofmann for the ballet Giselle at Basler Freilichtspiele in 1959. At first glance, we likely notice the pirouetting ballet dancer in the background. The blurriness of the photograph conveys the dancer’s dynamism and accentuates the silhouettes formed by her posture. The title of the ballet is vertically aligned on the left side of the poster in large font, effectively utilizing the negative space. Event-related information, such as the performance time and venue, is arranged horizontally in the top left corner. The entire poster features sans-serif text, with a black-and-white color scheme providing a minimalist base tone.

By analyzing the creative motives behind these formal elements, we can observe that the asymmetric layout facilitates readability and ensures the message is effectively communicated. The sans-serif text and the simplicity of the monochrome palette minimize distractions and evoke a sense of minimalism. The connection between various forms—layout, typography, color, and more—can be individually linked to specific genres. 18

18

These formal elements fall into distinct functional categories, which can be considered sub-categories within graphic design. Each category corresponds to its own genre.

However, from a macroscopic perspective, these elements share the overarching function of delivering messages directly, simply, and clearly. This broader function aligns the work with the main genre of Internationalist Graphic Design.

19

19

In art history, the suffix -ism is commonly used to classify works. Notably, within the current framework, -ism can denote either style or genre, depending on the context. This distinction hinges on whether the speaker intends to refer merely to a cluster of formal features or to include the anticipated motives underlying the creative actions.

This design arrangement allows the background photograph to captivate attention seamlessly. Most importantly, the design achieves this subtly and imperceptibly. Hofmann masterfully embodies the essence of Internationalism: a design that becomes an almost invisible conduit, enabling the dynamism and elegance of the ballet dancer to appear before the viewer as if through a transparent membrane. This intuitive quality is what profoundly resonates with audiences. It also demonstrates how the selection of photographic materials determines whether a work achieves the status of a classic. Without high-quality materials, even the most skillful allocation of forms will render the work hollow. Conversely, this poster exemplifies how superior graphic design is constructed through the interplay of materials and formal elements, ultimately presenting audiences with an aesthetic experience imbued with beauty.

This bottom-up approach to art history allows us to uncover the details of the creative actions underlying a work’s aesthetic experience through the analysis of style, providing a bird’s-eye view of its functional aspects. Understanding genre through creative actions clarifies how the creator’s purpose influences our interpretation of the work. Once the work is categorized into a genre, we can evaluate whether its formal elements are sufficient to fulfill its functions, thereby enabling an accurate interpretation.

This concept of genre broadens discussions of functional beauty. 20

20

This article clarifies several key concepts: Theme pertains to the content of a picture—its main objects, events, or narrative—essentially, what the picture presents to us. Style refers to the way a creator imparts a particular tone or flavor to the picture while expressing a theme, linking the aesthetic experience of the work to its formal features. A functional category relates more closely to the medium (e.g., poster, book cover, album cover) and the theme of the picture, indicating the appropriate functions for conveying thematic information through different media. Genre, in contrast, signifies the function of a specific style employed to depict pictures with a particular theme, focusing on the audience’s experiential reception of the images.

Understanding the functions of graphic design through genre relies on grasping both the theme and creative style of the work. Themes allow us to categorize the intended pattern of messages the designer seeks to communicate, while the analysis of style reveals how the designer, through their creative approach, conveys specific messages and experiences. This perspective moves beyond the transcendental concerns of philosophical aesthetics to an immanent analysis, sorting out how graphic design organizes materials that provide aesthetic experiences within the framework of art history.

With this understanding, we engage in a two-way analysis of iconography and iconology. Iconography categorizes pictorial patterns associated with different themes, while iconological analysis refines these categorizations by incorporating the concept of genre. This reciprocal process improves documentation and classification. Through the determination of genre, we can clarify the purpose of creations with specific themes expressed in particular styles, evaluating whether the designer’s practices—such as the selection and arrangement of materials—successfully realize the intended functions. Finally, we can assess the aesthetic value of a work based on how well its functions have been realized. 21

21

The necessity of beginning the aesthetic analysis of graphic design with iconography stems from the dependency of graphic design aesthetics on genre analysis. Since genre is derived from the analysis of style, understanding graphic design as a creative plan requires the ability to describe the actions executed according to that plan. Without such descriptions, how can the plan itself be understood?

This approach, which bridges art history and philosophical aesthetics, addresses the shortcomings of functional beauty theory while offering a comprehensive framework for appreciating graphic design. It demonstrates how designs achieve their functions through the aesthetic experiences enabled by their materials.

References

Abell, C. (2015). Genre, Interpretation and Evaluation. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 115(1pt1), 25–40.

Gombrich, E. H. (1972). Symbolic images (Vol. 2). Phaidon.

Mitchell, W. J. T. (1987). Iconology: image, text, ideology. University of Chicago Press.

Mitchell, W. J. T. (2015). Image science. University of Chicago Press.

Panofsky, E. (1983). Meaning in the visual arts. The University of Chicago Press.

Robb, D. M. (1936). The Iconography of the Annunciation in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries. The Art Bulletin, 18(4), 480–526.

Triggs, T. (2009). Designing graphic design history. Journal of Design History, 22(4), 325–340.

Triggs, T. (2011). Graphic design history: Past, present, and future. Design Issues, 27(1), 3–6.

Walton, K. (1987). Style and the Products and Processes of Art (B. Lang (ed.)). Cornell University Press.

Abell, C. (2015). Genre, Interpretation and Evaluation. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 115(1pt1), 25–40.

Gombrich, E. H. (1972). Symbolic images (Vol. 2). Phaidon.

Mitchell, W. J. T. (1987). Iconology: image, text, ideology. University of Chicago Press.

Mitchell, W. J. T. (2015). Image science. University of Chicago Press.

Panofsky, E. (1983). Meaning in the visual arts. The University of Chicago Press.

Robb, D. M. (1936). The Iconography of the Annunciation in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries. The Art Bulletin, 18(4), 480–526.

Triggs, T. (2009). Designing graphic design history. Journal of Design History, 22(4), 325–340.

Triggs, T. (2011). Graphic design history: Past, present, and future. Design Issues, 27(1), 3–6.

Walton, K. (1987). Style and the Products and Processes of Art (B. Lang (ed.)). Cornell University Press.

Copyright © 2019–2024 Taipei Art Direction & Design Assoc. All rights reserved.

Website designed and developed by Yaode JN︎︎︎. Running on Cargo︎︎︎.

Website designed and developed by Yaode JN︎︎︎. Running on Cargo︎︎︎.

Copyright © 2022 Taipei Art Direction & Design Assoc. All rights reserved.

Website designed and developed by Yaode JN︎︎︎. Running on Cargo︎︎︎

Website designed and developed by Yaode JN︎︎︎. Running on Cargo︎︎︎